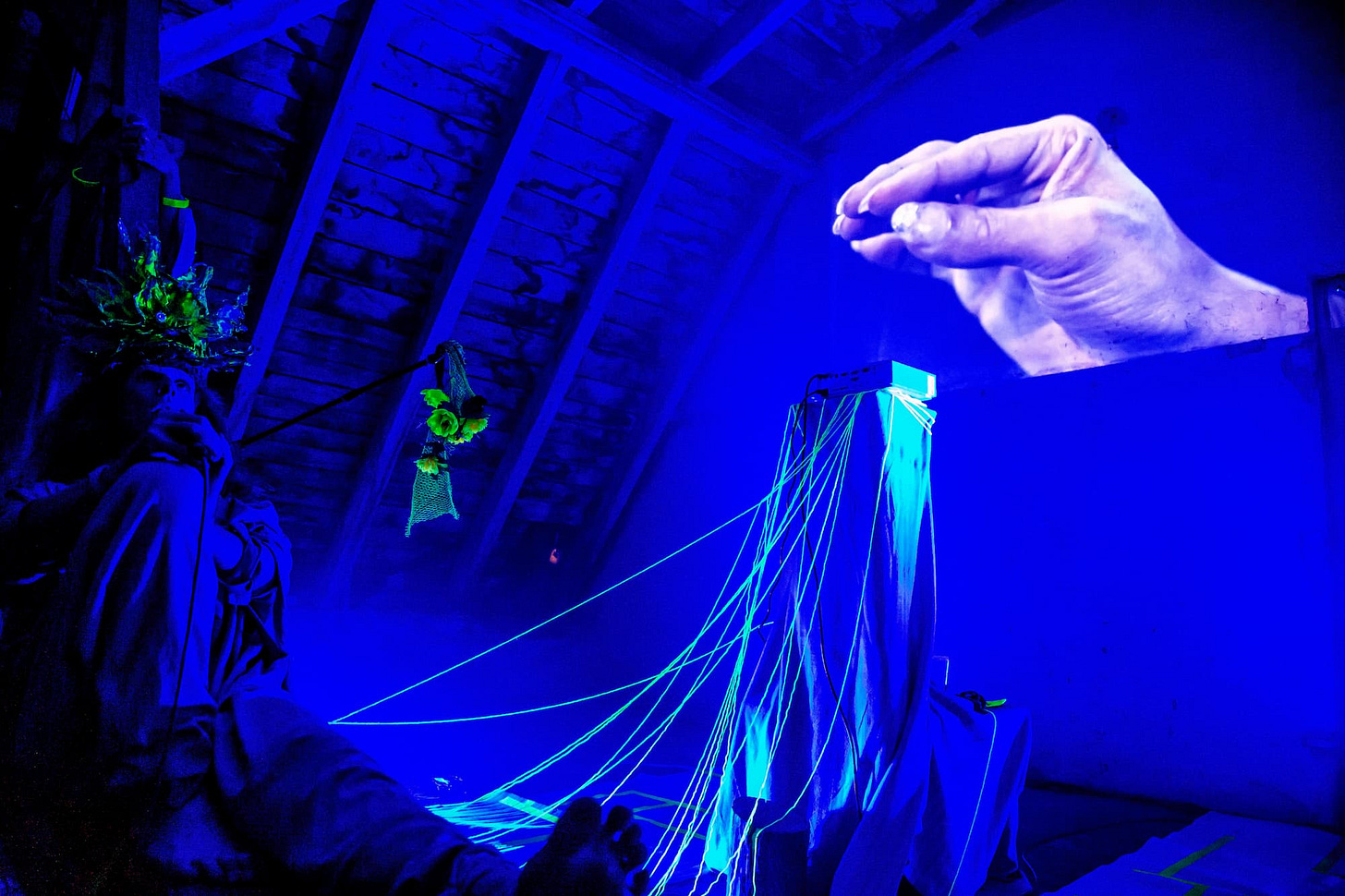

HYENAZ on silencing, aging, and the implicated body on stage

Read our interview by journalist Davide Gritti ahead of our Automine Italy tour

Ahead of our short tour in Italy next weekend, we had a wide ranging interview with journalist Davide Gritti covering artistic censorship in Germany, aging, and how what is worn on the body on stage implicates and complicates the performer. The interview is published in Italian here: https://www.performatorio.it/ideas-through-the-human-body/, but we wanted to share with you an english language version, which you can find below.

The dates of our Automine tour are:

12 May 2024: Festa Delle Transumanze, Masseria Jesce, Altamura

18 May 2024: Performatorio, Bergamo, Italy

Hope to see you there.

HYENAZ on silencing, aging, and the implicated body on stage

Interview by Davide Gritte

Davide: What does it mean to be an artist today? I'm not thinking about the definition of an artist, but more of having to deal with museums, foundation, galleries, all these kind of entities, and also the public.

Adrienne: I have a lot of skepticism about the public funding of the arts: that it can function very much as a kind of control mechanism. I've observed this with regards to my own caution over the years to speak out about what was happening in Palestine and in Gaza. In Germany there are resolutions in state and federal parliaments that forbid any kind of public support going to people associated with the boycott divestment sanctions movement. Although these have been successfully challenged in many courts, this has had a massive chilling effect on free speech, not only for people who support BDS. You don't know how curator A in gallery B will interpret the resolution, because they are also in the dark. So you end up playing a kind of 4D chess, running simulations in your mind about people you don't know and what they might be thinking.

I'm at the point now where I've decided that I don't care whether my speech affects my ability to get public funding. And I just feel a massive sense of ease. I feel more able to focus on the kinds of work that I would like to create. Kate and I want our work to confront the war machine, examine how art undermine its functioning and in the long term dismantle it.

Kate: I do think that the mechanism of control has always been present, not only to silence pro-Palestine voices, but also for other topics like sex work, even queerness at certain times, the anti-war movement. The way that our capitalist system is, in order for there to be that pool of money, there must be some exploitation. When you follow the money, there's something at the end that is not that great, that's to the military machine, to control mechanisms, to borders of who is legal and illegal. As long as our money is tied to those institutions and as long as our art is tied to capitalism at all, funding will always place restrictions and silencing on what can be said.

The paradox is that I can't survive in this world working for nothing. A lot of the projects I love the most I get paid nothing for. And I feel a lot of freedom in it. But it doesn't help me pay my rent. So then do I take a job like a bar job, a waitressing job, sex work…? But that limits how much we can deeply invest in our artwork.

In some ways I'd say I call myself lucky that I've never been completely inside the funding system. Most of our work is self-funded and I think it affords us a little bit more freedom and allows us to feel a little bit less afraid to speak out because we don't have as much to lose.

Davide: What about the body? I mean, your body and the body of the people outside - how does this interact with this thing of being free to do art?

Kate: I do feel like one of my survival coping mechanisms has been to create a system where I could use the work and the hustle to bring something back to my own body. Like, I couldn't afford taking dance classes, but I could start working a lot of dance jobs. I would think, OK, this is an opportunity for me to have a workout. This is also an opportunity for me to explore through my body, a chance to practice improvisation and thinking about music.

Or if I can't afford a taxi, I can ride my bike an hour across town and and I'm able to get a bit of adrenaline and exercise and free my mind from stress. On tour, we try to take trains which is better for This slow movement gives my mind a different sense of how time operates. You see the landscape change. You understand more what distance really is. So I try to look at work as an opportunity to encounter my body in a way that can also give something back.

Adrienne: I was also thinking about the finitude of our bodies, that our bodies are always wearing out, that they are approaching the point where the unity of energy and metabolism that makes me what I am, will cease to exist.

People respond to this in different ways. Some people go, well, I have this power and ability now and I'm going to use it to the fullest extent that I can, to live a life that's meaningful to me, to create what's meaningful to me, to push my body in different directions that I might not be able to later on. Of course with aging, there's also wisdom, and the relationship between wisdom and your body allows you to do different things. The body experience that I aspire to really embraces what is happening right now and make the most of.

The other way of responding is built on the illusion that there can be security for the body. This has to do with acquiring assets, acquiring income, acquiring cultural capital, so that the body is an immense and impenetrable fortress against aging, poverty, and death.

And, as we know, its not only the unity of our own individual bodies that is running out. The unity of the collective body of our society and the environment is also depleting. It's slipping away and we don't know what that will look like in 20 or 30 years. So I urge myself then to not try to create the body as the fortress against time.

Davide: You all make me think for the first time about the connection between body and youth, especially in the sphere of music. I realized that there is this immediate connection between being a performative body and a certain value of youth, that youth is another kind of capital.

Kate: I think we have to really work to resist this. I mean of course I think it's wonderful the deep discipline in certain dancers' bodies, where they work towards a kind of perfection or an ultimate flexibility or getting that position exactly right. But the idea that the body reaches the climax and then the only thing that comes after that is a fall … that seems horrible.

Our bodies, from the time we're 18, are changing all the time. You notice it changes when you're 25 already. And then it changes when you're 30 and then 35 and 40. There's no straight marker of when you suddenly old, right? It's a process. So I think we can resist the idea of trying to always outdo ourselves. Perhaps there's something not necessarily linear or progressive happening, that what the body is capable of doing is always different and changing. As we get older, as the body is getting fatter, as the body is getting thinner, maybe our hormones are also making it look more sort of trans in some ways so we look more androgynous or we cross gendered lines. If we are very explicit about what it is to be a changing body over time then this can be quite an interesting kind of performance on stage. I think of my idols like Kazu Ono, the Butoh dancer. So much of his most celebrated work is from his old age right up until he died.

Davide: I have the impression that in many cases the aesthetic is more limited than all the cultural references one could have. How do you connect your cultural references and ideas with the aesthetic that you use to make them visible to the audience? How does this process work for you?

Kate: One problem in physical performance is what to wear on the body. Sometimes a thing I put on my body might signify something different to an audience member than I had intended. For a long time we used to shave our heads and wear silver body paint. It was this alien and celestial thing and it brought along with it the idea of undoing gender. And then we invited some co-dancers to also have their heads shaved and be silver bodied. I loved how it looked. And I also thought, oh, does this look like we're some kind of cult? And also: is this obfuscating my white skin? Is that somehow negating the idea of race as if we're somehow beyond that? It's so important to continuously engage with discourses of race and colorism; so we've also kind of let go of using body paint no matter what the color.

Adrienne: We have our ideas, but then the body is the way that we filter our ideas into reality. And you have to let go to some degree the control over how things are going to be interpreted and seen by others.

I can give you the example of my nephew who is turning three. And his mother is pregnant again. And when she was first pregnant and they told him about it, he started to say, "oh now I have a baby". And he was having us touch his belly and listen to his belly. For me, this was a kind of performance he was giving. I don't know if he literally believed he was going to have a baby or not. But he had all these ideas, these dilemmas probably about change in his life and his mother's body changing and the presence of a new entity. And the way he could express that was through this aesthetic gesture: I’m having a baby; I'm going to perform pregnancy for myself and for all of us.

When I watch his performance, I don't know exactly what he's thinking about. And in a sense it doesn't matter, because he moved me, made me reflect on what it's like for a child to have a sibling enter their life, made me reflect on my relationship to my own body and the way that I can't actually become pregnant or carry a child.

He had his intentions, his ideas and he manifested them in a certain way. And then it's up to me as his audience member to project onto that. And the performance works if that dialogue touches us on a deep level and changes the way we think.